Pro Bike: How Graham Jarvis sets up his Husqvarna TE 300i

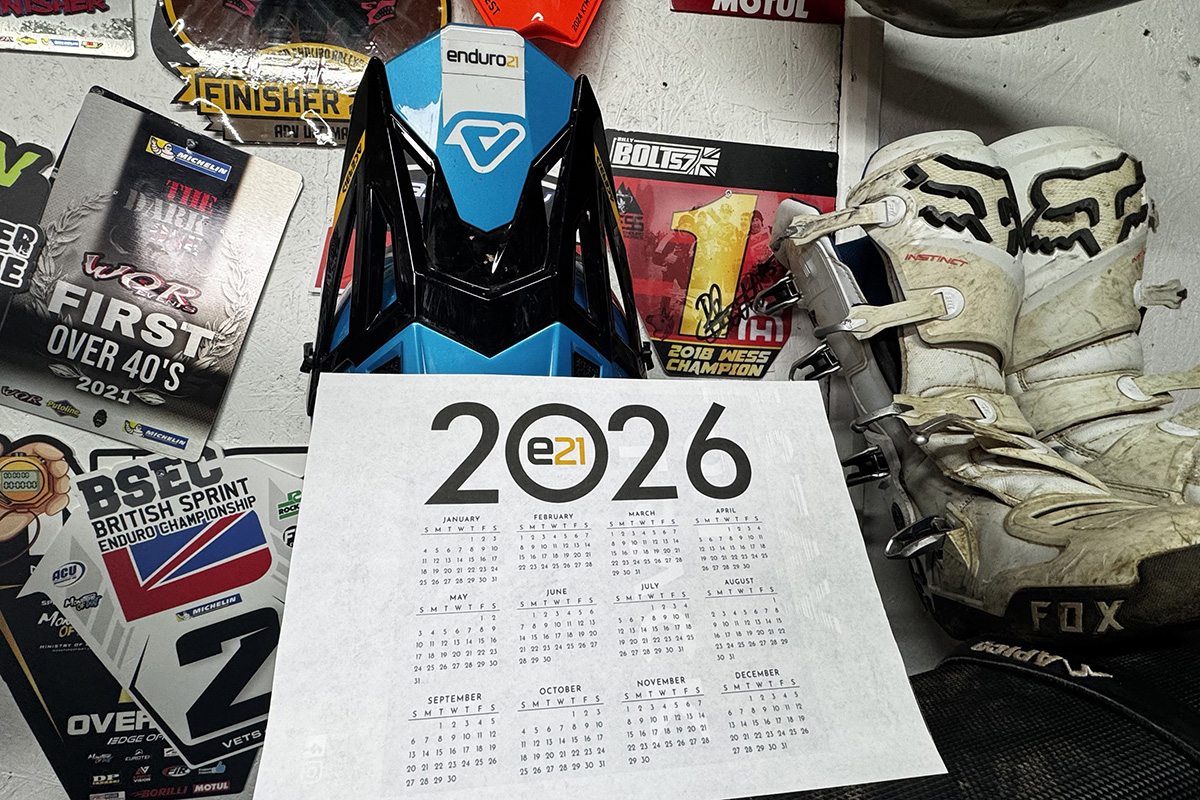

We’ve revisited an older Enduro21 story from 2018 looking at the details behind Graham Jarvis’ Husqvarna’s TE300i and how the master transitioned from carburettor model, tailoring the fuel-injected 300 two-stroke to Extreme Enduro and the WESS Championship.

While the chassis, suspension and hard parts remained largely untouched over the previous carburettor model, Graham Jarvis’s right-hand man, Damien Butler, tells us the work on the fuel-injected bikes was meticulous to get it set up exactly to the King of Hard Enduro’s liking.

Damo’ takes us back to that transition period when the fuel-injected two-stroke bikes were new and undergoing development to hone them for Extreme Enduro. Eventually they got the Husqvarna TE300i “on the money” but they had a lot to learn along the way…

Learning the art of fuel injection

Damien Butler: Compared to the carburettor model we noticed the characteristics of a faster track do suit the fuel injected model more than a slower riding course, which leans more towards the carb. However, that’s offset by the fact that the fuel injected bike, when put head-to-head on a hill climb with the carb model, has unbelievable traction.

A big benefit of the fuel injection system is that the engine is always running crisp and clean. On slow, technical riding it doesn’t load up and doesn’t require that usual big rev to clear it out before hitting an obstacle. And that’s important, especially with racing so tight now. We have found that when you chop the throttle on a really fast section there is a slight delay, but it’s fairly minuscule.

Naturally, there’s a play-off between both models, but with each test there’s a bigger step taken in the right direction.

A big benefit of the fuel injection system is that the engine is always running crisp and clean. On slow, technical riding it doesn’t load up and doesn’t require that usual big rev to clear it out before hitting an obstacle.

And that’s important, especially with racing so tight now. We have found that when you chop the throttle on a really fast section there is a slight delay, but it’s fairly minuscule. Naturally, there’s a play-off between both models, but with each test there’s a bigger step taken in the right direction.

The fuel economy is unreal. The bike wastes considerably less fuel than the carbed model and even with the same fuel tank as the ’17 bike, we’re finding we don’t need to refuel during a three hour race. For the exhaust system we run the standard front pipe, with the FMF 2.1 Hardcore titanium silencer.

The one pictured is actually the mark 2 version in that it is slightly longer than the previous model (which Jarvis and team-mate Billy Bolt helped develop with FMF Racing for the fuel injected bikes).

Getting the best of both worlds from the suspension

Graham runs a set of 48mm WP Cone Valve forks and Traxx shock on the rear. The shock has a light spring fitted, 42 weight rated, which is two rates lower than anybody. But there’s also some different internals in the shock to offset that. Overall, Graham runs the softest setting of all riders, but the setup still allows for fast riding.

When you ride it initially feels like a trials bike during the first third of travel, but as speed increases, the resistance ramps up and it can take some really big hits. We’ve taken it to our local motocross track — Fat Cats — and comfortably cleared some of the biggest jumps on the track without it bottoming out and whacking the ground.

That’s the result of a lot of work between Graham and Paul at WP. A lot of riders have tested our settings that Graham’s developed and quite like it too.

The triple clamps are Xtrig Rocs and generally we set the fork at about the third or fourth ring in the clamps.

She’s full manual, baby

Graham doesn’t use an automatic clutch. It’s a question we’re asked almost every race weekend. What he runs is the Rekluse Manual aluminium billet clutch basket and the Rekluse pressure plate with standard clutch plates. We also fit the Rekluse clutch cover for added protection because it’s much stronger over the standard cover.

We run standard radiators and cooling fan. We fit the Samco silicon hoses because they are stronger and expand less. Basically, this means the coolant levels don’t vary with operating temperatures. Transmission is a six-speed standard ratio gearbox with 13/50 sprockets by Superspox. New for this year is the RK chain.

Stopping Power

For braking, the setup is a Brembo Factory SXS caliper on the front, with the standard Husqvarna caliper on the rear because Graham found the rear braked too strongly for his liking.

The discs are from what the guys used in the World Enduro series last year. The idea of the cut-pattern on the rear is to help avoid the disc bending on rocks. Also, the slave cylinder is the factory version, which doesn’t have glass window to avoid breakage.

Lessons learned from Sea to Sky crash

After Graham’s crash at Sea to Sky, where the clutch perch broke, we’ve switched to the Teflon-bush clutch and front brake clamps available in the Power Parts catalogue. With the levers positioned tight and firmly, the teflon allows the clamp to move in the event of a crash. I put some grip tape on his levers for better control.

We run the standard Husqvarna Pro Taper handlebar, positioned level in line with the forks like most riders. It’s quite a low bar with a wide sweep. Grips are the 50/50 diamond waffle from Pro Taper.

Graham likes the Enduro Engineering brake pedal with brake snake attached. We’ve found it less rigid than standard, so will therefore bend before it brakes. Raptor supply the foot pegs. They’re a beefy set of titanium pegs for added grip and are positioned 10mm back and 10mm lower over standard foot pegs.

Additional parts include the Supersprox steel tooth rear sprocket (50 teeth) and (at the time) the SXS skid plate with shark protector linkage fin, TM Engineering chain block, Zip Tye disc guard, grippy seat cover and pull straps.