Everything you never thought you needed to know about Galfer brakes

Have you ever wondered how brakes are made and how they work? Galfer invited Enduro21 to their 6000m2 Spanish factory for a look at the technology behind the discs and pads helping Brad Freeman, Steve Holcombe and Jonny Walker at the top of the EnduroGP and Hard Enduro World Championships.

The Circuit de Catalunya is pretty famous if you’re into MotoGP or F1 racing. It’s located on a hill just north of Barcelona, in a busy hub of motor industry in the top corner of Spain where the likes of HRC Honda base their off-road race teams, GASGAS, and numerous off-road parts manufacturers are based.

A leading supplier across the motor industry, Galfer is also based in this little hotspot of Europe where they design, develop and manufacture discs (rotors), pads, brake lines and more for a large portion of the off-road market plus many race teams and riders from Beta, KTM, TM Racing, Husqvarna, Sherco, Rieju and now Triumph too.

Going fast on an enduro bike is important to some at least but being able to brake and be in control is important to everyone. How are brake discs and pads made and what’s the technology behind them? Enduro21 hopped on the Galfer tour bus with Steve Holcombe to find out…

Overheating, the No1 enemy

“Heat and dissipation” are key factors says Ivo Martin, Galfer’s sales manager who explains “overheating is the real enemy” of brake pads or the “friction material” as they call it here.

“If the brakes get too hot the pads and the disc have to work harder. If you take care of the overheating, you solve all the problems,” adds Ivo.

Galfer was founded in 1952 which means there’s a great tradition and experience in the science and the mechanics of braking in these walls. A tradition which stretches across many generations of models in all off-road sectors – and these days E-bikes too.

It is refreshing to find that Galfer focus on what they know, chiefly brake discs and pads plus a few other components. They have always limited themselves to their core products rather than branching out into master cylinders for example. The reason? They don’t want to compete with other manufacturers who they supply so work with and not against their partners.

Which brakes does Steve Holcombe use?

The seven-time world champion Steve Holcombe, one of the best-known faces from Galfer’s long list of supported riders – alongside his teammate, 2021 EnduroGP World Champion Brad Freeman – was at the factory with us and explained what he fits to his bikes.

With the whole range of Galfer’s products at his disposal, Steve says he chooses the DF814RW front rotor, without a core, “it’s more resistant and has a consistent and strong braking power. I use it in every type terrain,” Steve says, “even in mud, because it’s really effective. At the back, I run the DF815WLL, solid disc. I love the feeling it gives.” That model is Galfer’s new rear solid rotor which has 5mm of thickness. As for brake pads, Steve uses the newest products from the Galfer catalogue, the 1396R sintered pads.

“Enduro riders tend to use the back brake quite a lot, Brad quite more than Steve,” Ivo explains, “and this type of disc gives them more security because it overheats less due to having more material than a ‘normal’ one.”

One finger to brake by design

Caught up and slightly lost in all the pandemic madness last year, Galfer developed that new brake pad designed specifically for off-road. The 1396R pads being used by Holcombe have a improved stopping power but aim by design to let the rider use just one finger on the front brake.

“We don’t want them to bite to hard causing the wheel to lock, in enduro that will normally mean crashing,” says Ivo, “but we want them to give a great feel, progressive so the rider knows when the wheel is going to lock.”

They also showed us another of their new products, the rear brake caliper holders or hangers for KTM, GASGAS and Husqvarna models which allows fitment of the Galfer oversize rear discs.

“KTM is really the only brand to run 220mm rear disc as standard and we think that they overheat too much.” Says Ivo. “So we have created a brake caliper hanger which lets owners fit a 240mm rotor, a bigger diameter for less overheating.”

Ivo told us that they’re pushing hard for this product for the next season, even if some enduro riders think that bigger discs are more vulnerable to impacts. “The pros are higher than the cons” he says.

How are brake pads made?

The process behind those little blocks of ‘stuff” on your brake pads is a bit science and a bit like cookery. Everything starts in a room full of bags with different elements and a mixer, where for obvious reason cameras aren’t allowed. It’s a place with an unmistakable smell of brakes hangs in the air and where Galfer bakes their secret mix.

The recipe for the brake pad friction material uses between 12 and 25 ingredients that turns into the block of stuff that will be attached to the metal backing plate later on.

In the case of the sintered pads this process is done by fusion between the plate, previously coated in copper, and the friction block. The process heats both elements to a semi-liquid state to fuse them.

Finally, a rectifier polishes the pad to achieve the correct thickness and take away any irregularities before they’re packed in pairs ready for distribution and sale.

“When Steve, Brad, Jonny, Kiara or any other official rider asks for parts, we don’t panic or send special products. We simply go to the warehouse, look for the reference number and ship them because they use the same pads or discs that you can buy in a shop,” Ivo says.

Brake discs, the process

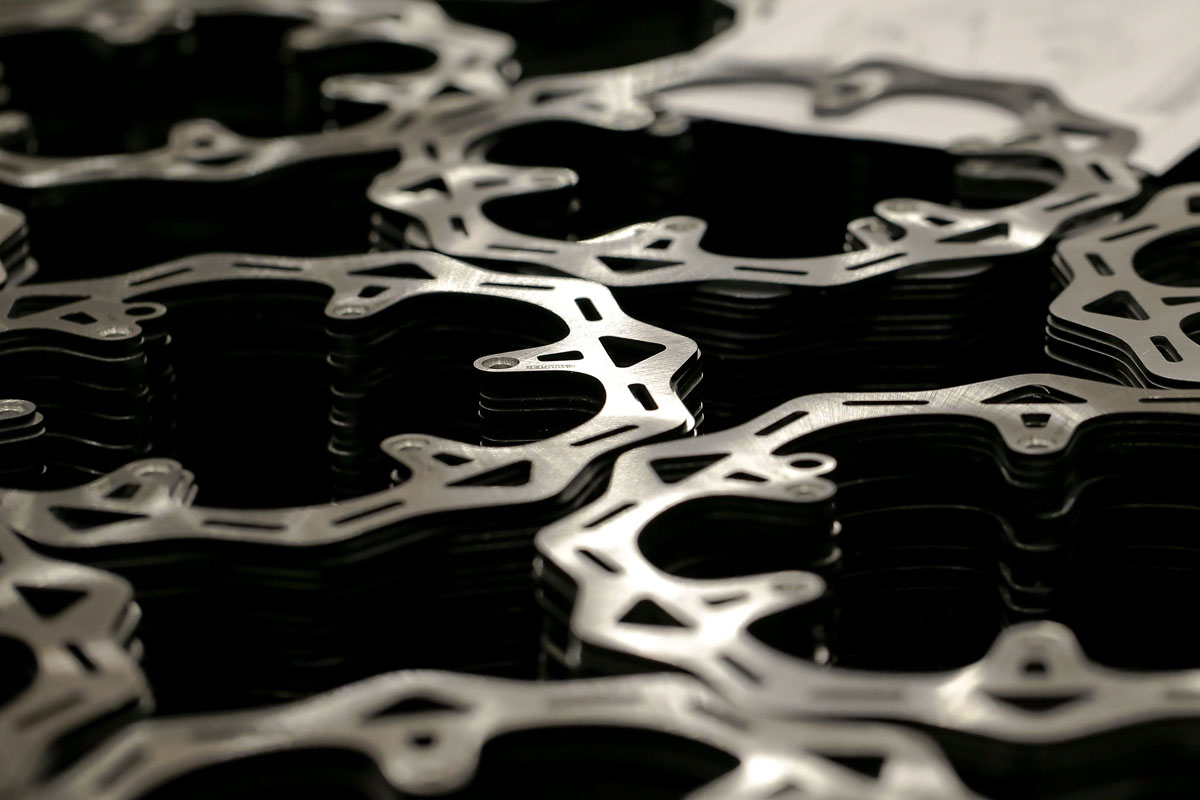

If the pads are like cooking then the disc manufacturing process is much more mechanical, though no less precise. Lasers precision cut the disc shapes out from big, high carbon steel sheets.

They then leave the factory for a couple of hours to another location nearby where they’re ‘tempered’ to near 1000 degrees to give the rotors the consistency and resistance needed for best performance and durability.

Once cooled, they’re back from the tempering process and go through an electrolysis process before being machined for the final time. The exterior parts get rounded to remove sharp edges and then, depending on the model, any holes in the disc are also cut before they install the core if the rotor is a floating type.

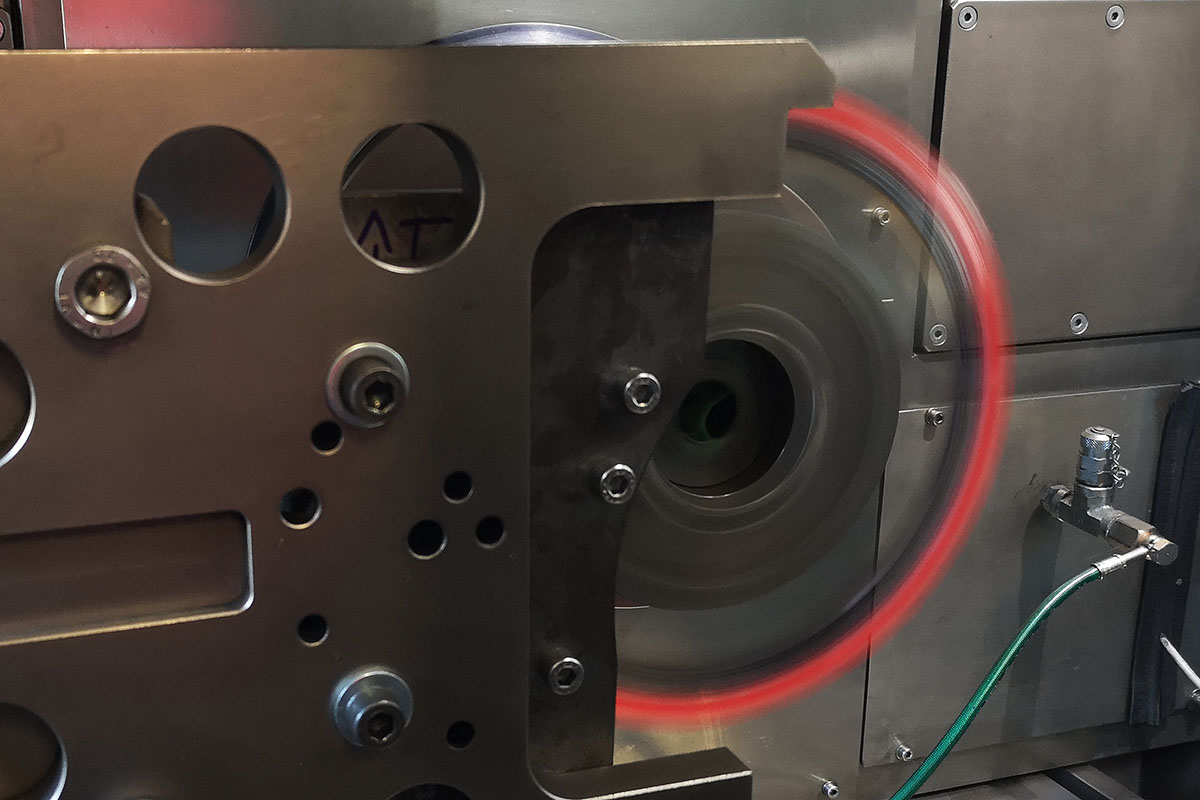

Final test: making the discs red hot

Not everything finishes with the discs being packed and shipped out. Galfer systematically tests all their product batches to make sure of quality and consistency.

The reasons to do it are simple: to avoid any defect and to track where any affected batch could be. Secondly this process is also where they gather data for the technical department so they can keep improving, developing, and innovating with their products.

Random product samples are carried out such as checking of joints between elements, the geometric flatness of the surfaces, the hardness of steel, accuracy of the friction materials, 3D dimensioning...it’s comprehensive because no-one wants these parts to be anything other than perfect.

They run different test but the most visual one is the friction test. The discs and the pads are made to work in machines, simulating real cycles until they are glowing red hot.

The recording of data does not end here. Is there anywhere to get better data than at the races? The factory riders like Holcombe and Freeman are part of the process but from 2022, Galfer will also have a Racing Service at the EnduroGP World Championship to help riders but also to develop the products.

“This way we’ll be able to know first-hand from the riders, mechanics and teams how to develop our ideas and products. Every Monday after each race we’ll have news and feedback to the factory”, adds Martini to conclude.

Enduro21 is keen to test these new products including the latest generation brake pads and the new disc hanger plus that oversized rear disc. As ever, we’ll fit the parts to our own bikes and check out let you know how we get on.

Photo Credit: Cristiano Morello + Lucas Mansur